On the morning of October 11, 2025, marking the 53rd anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between China and Germany, the Third “Humboldt Day” International Forum welcomed a cross-linguistic and cross-disciplinary feast of world literature and culture in Changsha, the “Star City.” Bathed in the gentle light of late summer and framed by the verdant scenery of Yuelu Mountain, the 613 multifunction hall of Tenglong Building was filled to capacity. Leading scholars from China and abroad gathered for the occasion, while students of the German Studies program at our university presented a meticulously choreographed collective recitation of Die zerbrochene Zunge (The Broken Tongue), an as-yet-unpublished novel by the renowned scholar Professor Ottmar Ette. With youthful voices, the students built a vibrant bridge of humanistic exchange between China and Germany.

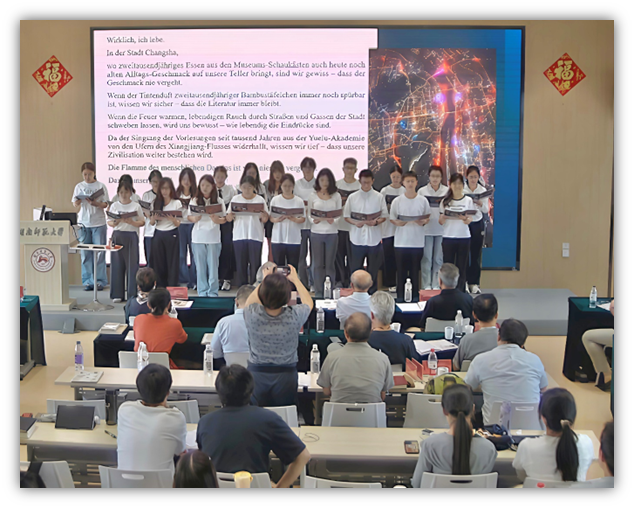

Die zerbrochene Zunge tells the story of a protagonist who travels the world in search of tastes and sensibilities that are gradually fading away. Through their own interpretation and performance, the students hoped to offer a distinctly Chinese response to this search. To highlight the novel’s themes and echo its multidimensional narrative perspective, the production team devoted careful thought and thorough preparation to every aspect of the program. Visually, Ms. Fanni designed a richly illustrated PowerPoint presentation that not only guided the bilingual Chinese–German recitation but also showcased the urban landscape of Changsha and emblematic images of Huxiang culture. Aurally, the performance featured an innovative segment in which the Chinese traditional instrument erhu was used to perform an excerpt from Johann Sebastian Bach’s Chaconne for solo violin, serving as a creative musical prelude to the literary recitation. Olfactorily, all performers wore a Changsha city–exclusive fragrance entitled “The Sound of Reading Rises beneath Yuelu Mountain.” To further intensify these multisensory stimuli, the program adopted a flash-mob format, with the reciting students standing among the audience rather than on the stage. Before the performance began, Ms. Fanni also lit a scented candle of the same fragrance at the lectern. Thus, amid flickering candlelight and a hall suffused with gentle aroma, the performance officially commenced.

Hosts Wu Yifan and Lan Ji’er first offered a brief introduction to Die zerbrochene Zunge and the theme of the recitation. Wu Yifan’s fluent and idiomatic German, combined with Lan Ji’er’s expressive and engaging narration, immediately captured the audience’s attention. This was followed by an erhu performance of the Chaconne excerpt by Liu Yuan, whose innovative interpretation, superb technique, and profound musical expression ushered the audience into the literary journey that followed.

The four excerpts of Die zerbrochene Zunge—“Mountain,” “World,” “I,” and “Life”—unfolded sequentially before the audience. As the microphone passed between performers and listeners, voices that were at times wistful, at times joyful, sometimes lyrical, sometimes impassioned flowed gently through the hall. With refined German proficiency and compelling stage presence, the students led the audience into an immersive artistic journey exploring perception, memory, perspective, existence, and the meaning of life. “Ich lebe (I live),” declared the final performer in a firm and resonant voice. At that moment, all performers stepped onto the stage and, accompanied by a low and flowing erhu melody, collectively recited the closing piece We Live, written jointly by faculty and students of our German Studies program specifically for this event. Drawing on Changsha’s three-thousand-year urban history, the everyday vitality of the modern city, and the millennia-old cultural lineage of Yuelu Mountain, the poem offered—through delicate and evocative language—a response from the land of Sanxiang and an echo of Huxiang culture to the novel’s quest for meaning. This ingeniously conceived finale deeply moved the audience: some listened intently, some fell into quiet reflection, while others captured the moment with their cameras. The atmosphere was both warm and electrifying.

When the students finally proclaimed, in powerful unison, “We live,” the audience could no longer contain its applause and cheers. Some experts spontaneously exclaimed “Bravo!” while others repeatedly called out “Zugabe!” (Encore!). When host Ms. Yi Jia mentioned that the students participating in the recitation had been studying German for only one year, another round of enthusiastic applause swept through the hall. Mr. Ole Engelhardt, Director of the Beijing Office of the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD), who subsequently delivered the closing remarks of this year’s Humboldt Day International Forum, also spoke highly of the students’ performance, remarking with admiration: “To speak after such a wonderful program is truly not an easy task!”

Professor Ottmar Ette himself was deeply moved. He made a special point of leaving the venue to speak personally with the students, repeatedly expressing his gratitude. “This program was absolutely outstanding! You are amazing!” he said sincerely. “You have found the most appropriate way to interpret my work. Your performance has truly brought my novel to life!” Such high praise filled the students with excitement and encouragement. Witnessing the heartwarming scene of world-class scholars and Chinese university students bowing to one another in mutual appreciation, Ms. Fanni, the program’s chief planner, was moved to tears.

After the forum concluded, Professor Alfred Hornung of Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz—Professor of American Studies, Member of the Academia Europaea, and President of the German Association for American Studies; Professor Zhang Longxi, internationally renowned scholar of comparative and world literature, Foreign Member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Letters, History and Antiquities, and Foreign Member of the Academia Europaea; Professor Stefanie Buchenau of Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne; Professor Feng Yalin and Professor Li Daxue of Sichuan International Studies University; Professor Li Xuetao, Dean of the School of History at Beijing Foreign Studies University and Member of the German National Academy of Sciences; Professor Ruan Wei of Hunan Normal University; and Professor Liu Yongqiang, Deputy Director of the Institute of German Studies at Zhejiang University—all offered warm congratulations on the program’s success and spoke highly of the students’ remarkable performance. Professor Buchenau humorously remarked, “The teaching quality of your German Studies program is truly impressive. My students would not be able to recite such a demanding text after just one year of learning German. Perhaps I should send them to Changsha first!” Professor Ruan Wei, a seasoned enthusiast of classical music, commented, “Performing Bach’s Chaconne on the erhu is an exceptionally creative idea!” In the days that followed, Professor Ette himself repeatedly expressed his admiration and gratitude to Ms. Fanni for the program’s high-level planning and outstanding execution.

Behind the brilliance of a single moment on stage lies years of dedication and weeks of meticulous preparation. Under Ms. Fanni’s careful coordination, doctoral student Long Qiyu from our Comparative Literature and Cross-Cultural Studies program completed the translation of the selected excerpts from Die zerbrochene Zunge during the summer break; undergraduate student Wan Yuxuan (Class of 2023) and alumnus Jiang Hao of the German Studies program repeatedly refined the wording of We Live; Professor Ole Döring reviewed and revised all German translations; undergraduate student Song Yujie (Class of 2022) and undergraduate student Liu Yuan (Class of 2024) carefully selected and diligently rehearsed the accompanying music. Meanwhile, 21 undergraduate students from the German Studies programs of the Classes of 2022 and 2023 devoted their spare time to intensive and in-depth rehearsals.

With teachers providing patient, word-by-word guidance, the students overcame challenges posed by rare vocabulary, complex sentence structures, and philosophical reflection. Through countless rounds of practice, correction, and collective coordination, their performance steadily improved. Even on the night before the event, Ms. Fanni and the students were still conducting on-site rehearsals in the 613 multifunction hall, repeatedly adjusting positioning and transitions to ensure that the program would be flawlessly presented within the allotted time.

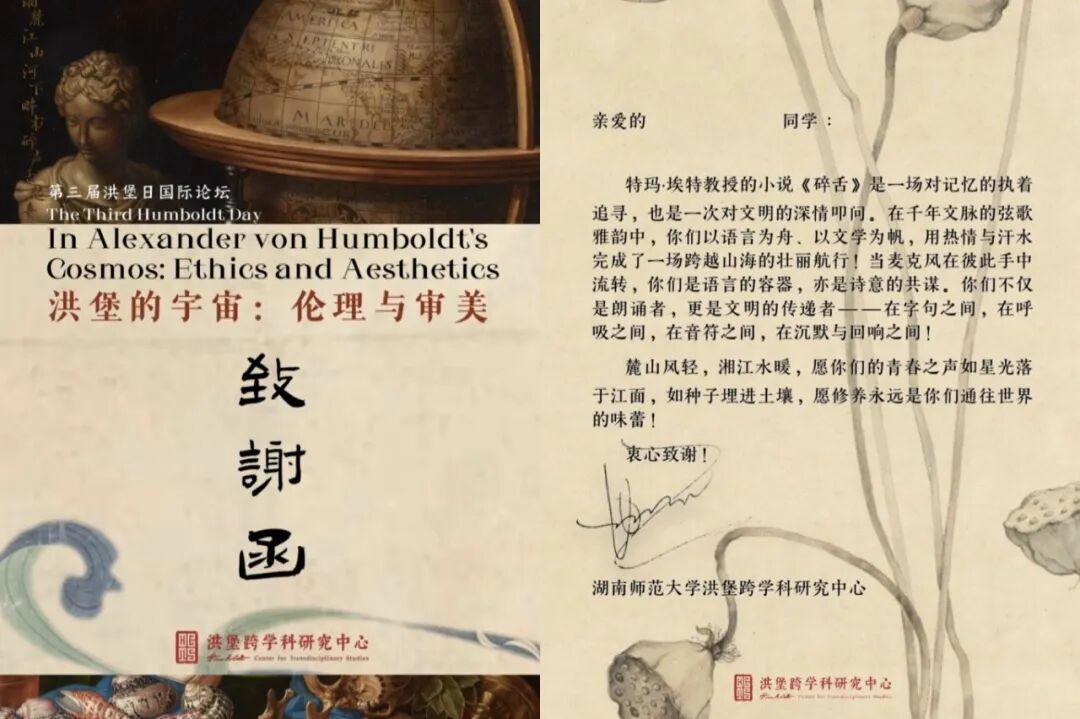

In recognition of the students’ outstanding performance and their positive contribution to Sino-German cultural exchange, Associate Professor Xia Kaiwei from the English Department and member of the Humboldt Interdisciplinary Research Center, together with Ms. Fanni, thoughtfully designed personalized letters of appreciation for each participating student, all signed by Professor Ette himself. This recognition from a distinguished scholar will continue to inspire the students to move forward with courage in their future studies and life journeys.

At this historic moment marking the 53rd anniversary of diplomatic relations between China and Germany, beneath Yuelu Mountain, this group of young followers of the “Humboldt spirit” used literature and art as their medium, voices as their testimony, and outstanding linguistic ability and humanistic cultivation to offer a vivid and moving example of deep cultural exchange and mutual learning between the two nations—together voicing their shared hopes for enduring friendship and the future development of human civilization.

The third “Humboldt Day” International Forum concluded amidst the sound oflear reading voices and gentle melodies. The student participants in this event recorded their inspirations and reflections in the form of essays, drawn from their experiences in reading and performing. These essays not only reflect their deep dialogue with Professor Ottmar Ette’s novel Broken Tongue, but also showcase their growth and reflections in the context of cross-cultural communication. Here, we present nine selected essays to offer a glimpse into the hearts of these young scholars and to see how they are bridging the cultural exchange between China and Germany through literature and art.

Broken Tongues Along the Banks of the Xiang River

Liu Xing

“Each beauty in its own way, the beauty of others’ beauty, and shared beauty for the common good, this is the ideal world,” said Fei Xiaotong, capturing the vision of harmonious coexistence of human civilization. However, looking at today’s world, despite the rapid flow of information, there seems to be an invisible Great Wall separating hearts. The barriers of isolationism, the ghosts of Cold War thinking, and the arrogance of cultural hegemony still try to divide, assimilate, and even defame the vibrant world. As the world faces disintegration, the recital under Mount Yuelu, with the powerful words from Broken Tongue, offers an answer from China and a resonance from Hunan culture. It also strikes a different note for the mutual learning of civilizations: “Civilization is like water; it thrives through blending. Thought is like light; only through mutual learning can it illuminate the future.”

At the beginning of the event, a piece of Bach’s Chaconne set the tone with its solemn and profound air. This Baroque violin masterpiece was reinterpreted with the erhu, retaining the original's meticulous structure and grand spiritual core, while also infusing the unique charm and deep emotional impact of Chinese traditional string music. The performer’s superb skill and deep understanding of music transformed the notes into an emotional torrent, slowly flowing through the hall, immediately capturing the ears and hearts of all listeners, perfectly preparing the audience for the upcoming literary journey.

Next, twenty-one students led us on a philosophical expedition through Professor Ottmar Ette’s Broken Tongue with their excellent German pronunciation. Heidegger once said, “Language is the house of being.” The powerful intonation of German, intertwined with the Eastern sound of silk and bamboo, gave us a deeper understanding—from the shock of soaring over Chimborazo Peak, to reflections on the world's diverse perspectives, and to the anguished question of one’s own existence. The students used their voices to perfectly embody the core message of the text: “Writing against the void and life proving existence.”

The recital began with “mountain.” As the voice rose, pursuing the lofty significance of Chimborazo Peak, we not only witnessed the passion of Humboldt-style scientific exploration, but also touched upon the shared reverence for the “sublime” in both Eastern and Western cultures. German philosopher Heidegger once said that humans should “dwell poetically on this earth,” and the calm and solid “earth” he referred to is just like the “mountain” that Confucius cherished: “The benevolent love mountains” because they are serene, heavy, nurturing all things without speaking. In the gaze upon mountains in Broken Tongue, we see Western philosophy’s awe and respect for nature, which coincides with the spirit of the Chinese phrase “gazing up at towering mountains.” At this moment, the mountain is no longer merely a geographic coordinate but a spiritual beacon shared by humanity.

The section shifted to the “world,” where a startling question in the text— “Perhaps this so-called one world does not exist at all. Has it already shattered into countless gazes upon it?”—thundered like a lightning strike. This is not a lament for non-existence, but a profound reflection on this diverse world. German philosopher Leibniz proposed “monadology,” suggesting that the world is made up of countless independent and reflective “monads,” each reflecting the universe from a unique perspective. As the saying goes, “A round bright moon, vast and boundless, its reflection touches every river.” The world is inherently multi-dimensional, with perspectives from both the passengers on a flight and the people in a slum; from the rich at a banquet to the poor struggling to survive. Recognizing this diversity and replacing the narrow “subjective view of the world” with the “objective view of the world” is the first step in breaking cultural barriers and eliminating discrimination. True cosmopolitanism is not about imposing a single standard upon all things but allowing every color in the kaleidoscope to shine brightly.

The climax of the recital focused on the blood-and-tears questioning of “I” and “life.” When the narrator questions, “Is this the taste of life?” and writes to combat the void, a sense of tragic grandeur transcending time and space arises. In the West, this is akin to Sartre’s existentialism of “free choice”: humans are thrown into a meaningless universe, yet must give themselves value through action, even in the face of the void. This mirrors Qu Yuan’s steadfastness on the banks of the Miluo River: “I follow what my heart cherishes, and though facing death, I regret not.” It is also the righteous spirit of “Life has always been fraught with death, yet let my loyal heart shine through the ages.” Professor Ette’s belief in “as long as writing continues, life will endure” is the code that allows human civilization to be passed down through the ages without end. Life is, after all, an endless creation and expression, the highest affirmation of existence.

When the recital transitioned into the collective section, the voices merged into a torrent, returning from philosophical heights to the mundane world. There was a sense of returning to simplicity. In the mellow and twisting melody of the erhu piece Sanmenxia Rhapsody, the students declared with firm voices: “Yes, I am alive.” This declaration, echoing through the ages, reverberates across time. In the ancient city of Changsha, the ancient foods sleeping in the museum windows, and the common flavors on the modern dining table, are connected by the same bloodline; the characters on the bamboo slips, still fresh, breathe alongside today’s poetry. This “taste that has never faded” inheritance is just as Heidegger said: “Language is the house of being”—through the same taste and writing, we dwell in the same spiritual home. The rising smoke from the city’s alleys, alongside the clear sound of reading from Yuelu Academy, forms the most poignant image of "human fire, forever continuing." In this moment, existentialism’s question “Why am I here?” perfectly blends with Confucianism’s earthly dedication: the meaning of existence is not on the other side of the void but right here, in the bubbling life, in every moment of cultural transmission. We live not only with our flesh and blood but as a ripple in the unending river of civilization, affirming the eternal continuation of culture with vibrant life.

Zhuangzi in Qiwulun said there are three kinds of sounds: “tianlai” (sounds of heaven), “dilai” (sounds of earth), and “renlai” (sounds of humans). Human sounds are produced by strings and wind instruments; earth sounds are natural, as the wind blows through thousands of holes; and heaven sounds are those created spontaneously according to the nature of things. This recital takes profound thoughts out of the study and into the world, becoming a bridge between cultures, truly attempting to turn “human sounds” into “heavenly sounds.” The German students, with sincerity as their furnace, language skills as their craft, fused German philosophy, Chinese music, and human confusion into one, ultimately playing a “silent music” that transcends language barriers. It tells us that culture is not a cold specimen in a museum but a flowing river; only by remaining in motion can it be passed on.

True communication is not the forced imposition of uniformity, but allowing every voice to sound freely in its own nature, eventually blending into a harmonious symphony. When the world’s clamor tries to build walls with separation, we choose to open a window through cultural exchange. We use language as a boat and civilization as an oar, neither arrogantly nor self-deprecatingly, allowing the profoundness of Chinese civilization and the depth of European thought to illuminate each other in equal dialogue. We must have the cultural confidence of “beauty in its own way,” standing firm in the roots and soul of Chinese civilization, and also have the open-mindedness of “beauty of others’ beauty,” embracing the multicolored world. Only then can we, in the waves of time, strike the water and hold the flying boat.

From “Broken Tongues” to Cultural Integration

Kuang Hongbo

When reciting excerpts from Broken Tongues, I suddenly understood what true “cross-cultural understanding” means. The themes of “losing one’s sense of taste” and “seeking the flavor of life” explored in this work are exactly the real experiences we face when learning a foreign language and encountering other cultures. The recited excerpts made me realize: the “taste” of culture needs to be personally experienced.

The protagonist in Professor Ette’s novel travels around the world searching for his lost sense of taste, which is very much like our process of learning German and understanding German culture. At first, the complex grammar and unfamiliar concepts were as perplexing as losing our “linguistic sense of taste.” But as I delved deeper into the text, I began to understand the special significance of Chimborazo Peak for the Germans and to grasp the profound observations about the gap between rich and poor in the novel. At that moment, German was no longer just cold words; it became a living language with warmth and cultural context.

What moved me most was the "shift in perspective." The novel repeatedly asks: “Is the world one, or is it countless?” As we recited the passages about the slums of Quito in German, I suddenly realized that we were looking through the window of the German language into a different society. When we accompanied the German text with erhu music, we infused this German story with Eastern understanding and emotion. True cultural exchange is not a one-way learning process but a bidirectional expansion of perspectives and fusion.

I am grateful for this experience, which taught me that language is a bridge and culture is a boat. We build bridges with German, and the rich cultural heritage of both sides is what carries us across. When the scent of books from the base of Yuelu Mountain fills the air in the venue, German literature and the thousand-year cultural lineage of Yuelu Academy miraculously intertwine. In that moment, I deeply felt that we were not simply “learning German culture,” but engaging in an equal, creative dialogue.

This activity has deepened my understanding of Sino-German cultural exchange. It is not about putting one culture into the container of another, but, like this activity, creating new and integrated cultural experiences. Our generation must become bridge builders and ferry people. I thank everyone who made this profound cultural experience possible. This experience will always inspire me to continue moving forward in the path of cross-cultural communication.

Small Stones, Big Ripples

Li Fuxin

To stand in a significant academic event, surrounded by professors and experts, and use the German I’ve learned to express my exploration and reflection on the boundaries of the universe, individual existence, and the human soul, was an incredible experience for me. The few minutes of recitation on stage were built upon countless rehearsals with my classmates offstage, and it encapsulated the essence of five thousand years of excellent Chinese traditional culture, as well as the hospitality of the great Eastern nation symbolized by the city of Changsha. An Erhu performance further connected China’s grand history with the philosophical inquiries of a German novel, creating an invisible bridge between foreign cultures. After the performance, experts praised our efforts. Although I did not feel I made a huge contribution, this is what the German major has given me—the ability to create bigger ripples than a small stone, which is a profound and silent sense of achievement and emotion.

The Bridge of Language, Connecting the World

Long Biao

This semester’s recitation at the Humboldt Day International Forum felt like a window suddenly opened, letting me see the broader landscape of language learning. When standing on stage reciting excerpts from Professor Ette’s Broken Tongues, those words, which were once printed on paper, suddenly gained warmth and weight. They were no longer just words and grammar to memorize, but became a bridge connecting different cultures.

The story of Broken Tongues hides universal emotions and confusions of humanity. When our voices echoed in the classroom, and I saw the foreign professors focused in the audience, I suddenly realized that the true charm of language lies not in “speaking,” but in “being understood.” We didn’t just read the German novel in German; before reciting it, we shared the story of Broken Tongues and the culture of Hunan in both Chinese and German. This made the performance feel infused with the essence of China. At that moment, language was no longer a barrier but a bridge—on one side stood our familiar cultural soil, and on the other, their curious gazes. We were standing on the bridge, transmitting stories and warmth across.

Another moment of the performance still warms my heart. When the strings of the Erhu were plucked and Bach’s Chaconne gently flowed, the marvelous fusion of the music was unforgettable. The smooth, flowing sounds of the Erhu, intertwined with Bach’s rigorous structure and profound emotions, merged harmoniously. This made me suddenly realize that language learning is never isolated; it is tightly connected with music, culture, and history. Just like the meeting of the Erhu and Western music—seemingly a clash of two cultures, but in reality, it’s a dialogue across time and space. Language learners should have this perspective, breaking cultural boundaries and exploring more diverse possibilities.

This event has given me a new understanding of the identity of a “language learner.” I once thought that learning a language was just for smooth communication, or for exams and work. But this experience showed me that language learners are more like bridge builders—we use language as a tool to build communication channels between different cultures; we use the knowledge we’ve acquired to tell the world China’s stories and bring the world’s stories back to China. This is not just the application of a skill, but a weighty responsibility.

Now, whenever I open my German textbooks, those words and sentences seem to have new meaning. They are no longer dry symbols but bricks waiting for me to build a stronger cultural bridge. I know the road ahead is long, but this experience has already illuminated my direction—to become a language learner with vision and responsibility, using the power of language to let the world hear China and let China see the world.

We Are Still Alive

Jiang Hao

By the Xiang River, the land that gave birth to the works of Qu Yuan and Jia Yi, the cultural lineage of Yuelu Mountain flows like the river itself, uninterrupted. At this moment, a group of German language students, bathed in the fragrance of a thousand years of academic heritage, are using language as their vessel, music as their sail, literature as their compass, and fragrance as their lighthouse, weaving a cultural symphony that crosses time and space at the intersection of Eastern and Western civilizations.

Travel is Humboldt’s philosophical journey to explore the world; Chaconne is Bach’s musical meditation on the universe. When German philosophical reflection meets Chinese artistic aesthetics, and when the light of Western reason illuminates the sea of Eastern wisdom, we touch the common pulse of human civilization in this cultural dialogue.

“I think, therefore I am”—Descartes’ philosophy gains new life in the East. Yes, we live—we live as bearers of civilization, we live as creators of culture.

In this city, which carries the genetic code of Chu culture:

When the ancient pottery in the museum’s showcase still evokes our primal longing for food, we witness the eternal truth of “food is the most important thing for the people” — the root of civilization is deeply planted in the fertile soil of life. When the ancient characters on unearthed bamboo slips can still communicate with our souls, we understand the profound meaning of “writing carries the way”—the power of thought can transcend the barriers of time and space. When the smoke rising from the streets of the ancient city still stirs our warm memories of home, we feel the real warmth of “human smoke”—the poetry of life is in these ordinary, daily moments. When the sounds of reading in Yuelu Academy still stir our hearts, we understand the noble mission of “establishing the heart for heaven and earth”—the fire of education lights the path for human progress. Here, whether it is a long-awaited reunion or a meeting as if for the first time, every encounter is a dialogue of civilization, every pause is a reverberation of history. Three thousand years of hindsight, ten thousand years of waiting. On this ancient and youthful land, we carry on and write the magnificent chapter of this era.

This is the charm of culture, this is the power of civilization. It keeps us awake through the passage of time and steadfast in the changes of history. It makes us realize that every era is the continuation of history, and every generation is the inheritance of civilization. On this land, history is fragile, for it is written on paper and painted on walls; yet it is strong because there will always be a group of people willing to guard its truth. In this sense, we are not just alive; we are continuing the life of an ancient civilization, writing a new chapter in human history. Our existence is civilization’s existence; our creation is history’s creation. This is the true meaning of “living”— innovating in the process of inheritance and inheriting in the process of innovation, so that the flame of civilization will forever burn and the wisdom of humanity will forever shine.

We live, we have always lived, and we will continue to live.

A Journey from “Broken Tongues” to the Sensory “Fullness”

Lan Jier

As the host of this German recitation cultural festival, reflecting on this event fills me with emotion and awe. It was far more than a literary recitation; it was a deep journey across language and the senses.

The excerpts from Ottar Ette’s unpublished novel Broken Tongues, carefully performed by my classmates, transformed into a collective life experience. The meticulously prepared and heartfelt recitations made us realize that language is not just a vehicle for meaning; it can itself become a sensory event. The central theme of “gradual loss of taste” in the work became tangible through the act of recitation. We were not only on a quest for one sensory experience, but also seeking the "fullness" of life itself, alongside the protagonist.

What impressed me most was the novel’s Cubist narrative style, which allowed us to see the world through multiple perspectives: the German geography professor who was thrilled by Chimborazo Peak, the indifferent Japanese climbers, and, most poignantly, the hidden perspectives of the people living on the margins of the Quito slums. This delicate presentation of shifting perspectives raised a fundamental question: Does a single world exist? Or is the world actually composed of countless, irreconcilable worlds, “stitched together by all of our gazes”? The recitation prompted us to examine our own way of perceiving the world.

The creative presentation of this event transformed the entire space into a sensory universe, creating a unique cultural fusion—just as the text suggests, this was a true cultural “confluence.” It was not merely an accompaniment, but a dialogical expression, showing how different art forms enrich each other and open up new layers of meaning.

For me, the climax was the specially created final passage of the event, which took the global reflection in Ette’s work and directed it toward our local reality in Changsha. “When the scent of two thousand-year-old bamboo slips is still in the air, we are convinced—literature is eternal.” These poetic lines lingered in the air. They reminded us that today’s search for meaning and taste is rooted in a millennia-old culture of writing, preserving, and passing down, much like the heritage held by Yuelu Academy. The poetry was experienced through the sense of smell, and this brilliant and unforgettable ending perfectly echoed the theme of the event.

As the host, I was fortunate not only to link the recitations together but also to witness the event unfold up close. I felt the focused faces of the reciters, the silence of the audience during the deepest passages, and the light of understanding in their eyes as the difficult sentences were perfectly rendered. This was a shared celebration—a community of teaching and learning, a community of recitation and listening, a community of German texts and Chinese context.

This event once again proved that literature is not an ivory tower. It is vibrant, piercing, sensory, and questioning. It allows us to rediscover the flavors of life while teaching us to see through the eyes of others. I am grateful to all the participants who together created this event, which not only allowed me to taste German through my tongue but also to savor the complex and rich flavors of life itself.

The Voice of Literature

Chen Hong

This year’s cultural festival was somewhat similar to previous ones, yet it carried a sense of new vitality. We participated in a special activity—reading excerpts from Mr. Ette’s novel aloud. To be honest, when I first received the chapters, I felt a bit uncertain, because the work was truly challenging. Every line was full of reflection, and reading it felt like delving into philosophical questions. Fortunately, the event was scheduled after the National Day holiday, giving me enough time to prepare.

Honestly, the entire process was not easy. I had to break down those complex, lengthy sentences into concise, readable short sentences while also capturing the rhythm and emotion of the text. Yet, in the end, we succeeded. After returning to campus, we successfully held the reading event. What moved me even more was that Mr. Ette personally came to express his gratitude. He said he was thankful for the way we interpreted his work.

I am very grateful and deeply cherish the opportunity our teachers gave us. This was not only a personal exercise but also a vivid cultural exchange. Reading Mr. Ette’s work aloud strengthened my courage and expressive skills, and it also gave me a deeper understanding of German literature.

From Listening to Resonance

Yu Lu

For my classmates and me, the true beginning of the cultural festival might have been when we wholeheartedly devoted ourselves to rehearsing our reading performance. We recited excerpts from Professor Ottmar Ette’s Die zerbrochene Zunge. I think, as we repeatedly practiced, trying to make every syllable carry weight, the line “Du lebst, solange Du schreibst” quietly flowed from the page into our life experience.

On stage, nervousness and concentration intertwined. Only when the final unified recitation ended and the audience applauded—and especially when we saw the teachers’ eyes glimmer with satisfaction—did we finally breathe a sigh of relief. We had never expected the resonance created by such dedication to be so moving. Professor Ette himself sought us out afterward. His sincere gratitude and heartfelt emotion even moved our mentor, Professor Fan.

At that moment, I deeply realized that language goes beyond being merely a tool of communication; it enables a cross-temporal, soul-stirring resonance. We were not only learners but, in a sense, became interlocutors and transmitters of meaning.

Literary Life Activated

Wan Shichang

This reading was not a simple recitation of text, but a journey of delving into the very texture of the work—a collective exploration of “how voice shapes meaning.” Professor Ottmar Ette’s The Broken Tongue is full of linguistic experimentation and cultural hybridity challenges. In the preparation process, we not only had to master the accuracy of pronunciation and intonation, but also deeply understand the emotions and philosophical reflections flowing beneath the fragmented narrative—on memory’s ruptures, the pursuit of identity, and the unreliability of narration itself.

When our voices merged in the space, linking those seemingly “broken” sentences together, I felt, in an unprecedented way, that the life of literature does not exist only on the silent page; it is reactivated in the breath and rhythm of reading aloud. Every pause, every emphasis, was our interpretation of the text. This shift from “visual reading” to “auditory and embodied participation” allowed me to grasp another dimension of language learning: it is not merely the decoding of information but also the resonance of emotion and the co-construction of meaning.